Queering a Path through the Universe: Sex & Love in Sci-Fi

by Courtney E. Morgan

There have been more and more representations of queer characters and relationships in mainstream media lately—more depictions of fully fleshed out, round protagonists, given fullness and complexity in their relationships and their narratives. Queer characters can be the leads in important movies, can win awards: Moonlight, Call Me By Your Name, Battle of the Sexes come to mind.[1] It’s a beautiful thing.

Queer cinema, of course, has been making incredible movies for decades, but there’s been a real shift, with queer characters and relationships becoming more common and normalized and even centered, in commercial films and TV shows in recent years. However, very few of these narratives offer really “happy” or positive endings for their characters—particularly rare are storylines with queer relationships thriving or even remaining intact at the end of the film.

This has something to do with genre, of course—these films mentioned aren’t exactly rom-coms—but I think it has equally as much to do with acceptance, or lack of, and the lingering (often blatant) homophobia still permeating our culture.

I think of an interview with Annie Proulx many years ago, after her novella, Brokeback Mountain, broke out onto the big screen. Brokeback Mountain, in both story and movie form, is a love story between two gay cowboys, set in Wyoming in the 1960s, and it ends with a horrific murder.

In an interview with the Paris Review, Proulx lamented: “I wish I’d never written the story. It’s just been the cause of hassle and problems and irritation since the film came out … So many people have completely misunderstood the story. I think it’s important to leave spaces in a story for readers to fill in from their own experience, but unfortunately the audience that Brokeback reached most strongly have powerful fantasy lives. And one of the reasons we keep the gates locked here is that a lot of men have decided that the story should have had a happy ending… They can’t bear the way it ends—they just can’t stand it. So they rewrite the story.”

I find this anecdote telling but also surprising—that men (both gay and hetero, but primarily hetero according to Proulx) so resisted the ending of the story: Jack White’s brutal and homophobic murder.

“They can’t understand that the story isn’t about Jack and Ennis. It’s about homophobia; it’s about a social situation; it’s about a place and a particular mindset and morality. They just don’t get it.”[2]

This does, of course, play into the “bury your gays” or “dead lesbian” tropes in television and film, which is problematic (not to mention easy).

But I think Proulx’s complaints begin to speak to way that art is descriptive and reflects back at us our own cultural values and norms. There can be no happy ending for Jack and Ennis within the confines of a homophobic world.

What I find interesting is that in films like Moonlight and Call Me By Your Name, the homophobia is there, it drives characters and directs their lives, but Elio and Oliver, Chiron and Kevin, still carve out moments of peace and calm, of deep human connection and love.

There are no happily-ever-afters, no, but there is space in the endings of Moonlight and Call Me, ambiguities that don’t close out happiness entirely. Something impossible in Brokeback Mountain; something impossible in that time period, perhaps. I believe that these new spacious endings for queer love stories reflect a wider cultural shift—a progression, I hope, the moral arc of the universe bending toward justice,[3] toward equality, slow and circuitous though that arc may be.

Homophobia is still a dark and present scepter in these stories, but it does not determine where they finish. Notably, though, it also (still) does not allow for a conclusive, happy ending.

There are other stories, however, where the mantel of homophobia, while not erased or denied, is thrown off, is overcome, or, perhaps a better word—is circumvented. In speculative[4] narratives, we begin to see the story possibilities expanded; the tropes subverted; homophobia and transphobia, transcended.

Speculative stories have the ability to imagine (and therefore affect?) the arc’s progression, and often that future looks quite bleak. But sometimes it is full of hope and joy.

The television show, Sense8, a speculative story set in our time and world (or one very close to it), includes gay, lesbian, and transgender characters, narratives, and love stories, with complexity, nuance, and depth—and all the saccharine joy of over-the-top romantic comedies to boot.

Queer characters and their love lives are given all the import and meaning of their hetero counterparts. Although it is set in a world very much like ours, I believe that it’s the story’s speculative elements, the twist of the homo-sensoriums—human-like beings that can psychically and physically share each others’ experiences—that creates the space and potential for such narratives to exist and to unfold.[5]

Author Ursula K. LeGuin wrote:[6] “As writers under repressive regimes have long understood, science fiction is particularly well suited to the indirect but intense examination of the political and moral status quo, since its tropes and metaphors (outer space, far future, etc.) allow the writer to look from a distance at what is actually very close at hand. As the scholar Darko Suvin said, science fiction is the mirror that lets us see the back of our own head.

“This is notably true when it comes to issues of gender. No other literary form has asked so many questions so usefully about the nature and construction of human gender, the actual and possible relation of the sexes in society.”

I’m interested in the potential speculative art has to look at where we currently stand, and also its capacity to explore hope and envision joy, especially for groups marginalized and harmed within our current system.

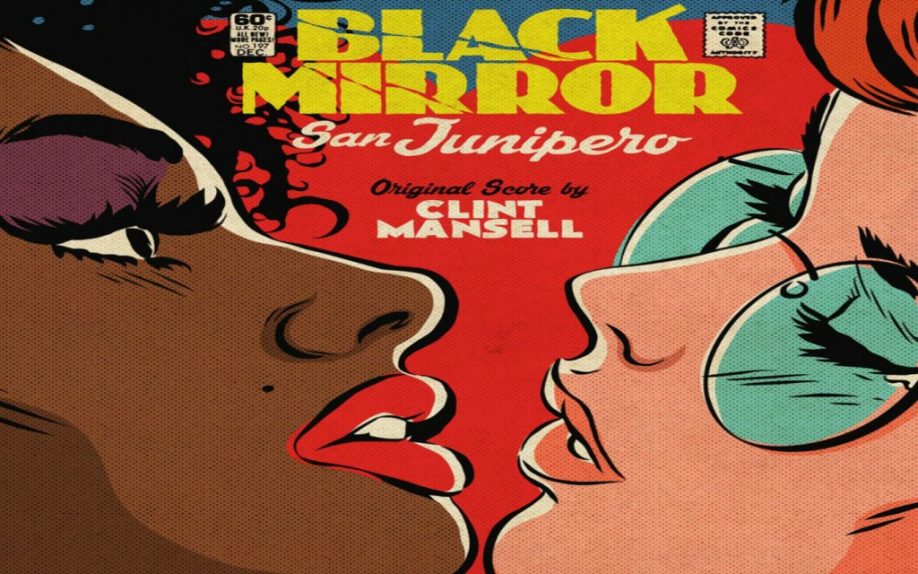

In “San Junipero,” an uncharacteristically rosy episode of the dark sci-fi TV series, Black Mirror, protagonists Yorkie and Kelly meet and fall in love in a simulated virtual world. After spending a good amount of the episode immersed in this alternate reality, we viewers learn that they are in fact aging and confined to nursing homes and hospitals in “real life,” and this virtual reality is a form of nostalgia therapy.

Yorkie, in a heart-wrenching narrative turn, is revealed to have been in a coma for the last forty years, since she was twenty-one and injured in an accident related to her family’s homophobic rejection of her. In San Junipero, however, she can not only live out the life she has missed, but can choose to love, be intimate with, and even marry whomever she chooses, without consequence.

The period piece elements reinforce the effect, but the fact that Yorkie and Kelly are given—are allowed to choose—a happy ending together speaks of a major cultural shift.[7]

But this is a shift that is allowed, that we viewers can accept, because it is in the future, because it is in a technological landscape that is different enough from ours. This is not where we are, perhaps, but it may be where we are going.

In creating at least some degree of distance from our current cultural relationship with sexual orientation, gender, and homophobia through the metaphors of virtual reality (San Junipero) and alternate biology (Sense8), as examples, speculative narratives are able to explore who and where we are, to show us the back of our heads, as it were, and to also move into new realms of possibility and imagining for who and what we have the potential to become.

We desperately need artists to engage with visions of reality that allow for joy and for happy endings for LGBTQ folks, for people of color, for women and femmes—without glossing over or negating the current conditions and problems. Speculative storytelling allows us to explore our present values and cultural consciousness, while carving out space and potential for other possibilities, including, perhaps most importantly, the fullness of human connection, love, and joy.

Now I just hope the Sense8 finale can deliver.

[1] Here’s a great list of more films in 2017.

[2] While Proulx’s complaints belie her own obsessive desire to control interpretations of her art (and the straight up grumpiness evident in many of her interviews), they also point to the willful ignorance of readers around the issues of homophobia. A desire for something better, yes, but also a level of denial, or unwillingness to confront a homophobic reality.

[3] “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Quoted by Martin Luther King, Jr. in a 1958 article, attributed to Theodore Parker.

[4] I use speculative as an umbrella term for sci-fi, fantasy, magical realism, any mode that steps outside the “real.”

[5] Although it’s not nothing that the show was canceled after two seasons, despite great ratings and Netflix’s promise not to end shows without completing narratives. And whatever claims were made about budget, etc., many fans were not convinced. Netflix has promised, however, to close the series with a two-hour special.

[6] In a letter of support for WisCon in 2006.

[7] There is some irony, of course, in the fact that they are indeed the “dead lesbians” of the trope—but through the subversion of death, the trope is also subverted, and they get their happily-ever-after, even if it’s in an alternate reality (/afterlife).

Courtney E. Morgan is the founder and managing editor at The Thought Erotic. Her collection of stories, The Seven Autopsies of Nora Hanneman, was a semi-finalist for the FC2 Ronald Sukenick Prize in Innovative Fiction and released from FC2 in 2017. She has also published work in Pleiades, Lunch Ticket, American Book Review and others. Find her at CourtneyEMorgan.com.

Courtney E. Morgan is the founder and managing editor at The Thought Erotic. Her collection of stories, The Seven Autopsies of Nora Hanneman, was a semi-finalist for the FC2 Ronald Sukenick Prize in Innovative Fiction and released from FC2 in 2017. She has also published work in Pleiades, Lunch Ticket, American Book Review and others. Find her at CourtneyEMorgan.com.

One thought on “Queering a Path through the Universe: Sex & Love in Sci-Fi”