by Matthew Pridham

In the Beginning—My Poly Predecessors

I blame the Bible.

This is the response that runs through my head every time I’m asked how I became a polyamorist. It is a snarky answer, the sort of thing one trots out in order to be provocative of either thought or a nice juicy argument, but there is some truth to it. I was born into a family and a sub-culture saturated with all things Biblical. Characters such as Jacob, David, and Solomon have been a part of my imaginative landscape as long as Darth Vader, Sam Spade, and the Gremlins have.

Taught to see these religious figures (mostly male, unfortunately, with the exception of standouts like Esther and Ruth) as models of virtue and godliness, I read their stories with the devotion of a fan. Sure, they fucked up: they ignored warnings their prophets had given them, they stole, lied, cheated. Some, like David, murdered innocents. Even when they were following the dictates of Jehovah, they leveled whole towns, slaughtered entire populations. If anything, this inculcated a taste for complex characters, for anti-heroes, outsiders, and, for lack of a better term, anti-villains (think Hannibal Lecter). Primarily, though, these characters came across as epitomes of strength, compassion, and spiritual character.

As I stumbled into puberty, however, another facet of these men caught my attention. Unlike my loving parents, unlike the members of the churches through which I passed, unlike even the dangerous liberals I was warned were destroying the moral fabric of the United States, an awful lot of my Bible heroes were married to more than one person. While plenty of these relationships came fraught with drama, the Bible (in this case, the books of the Tanakh, later rebranded as the “Old Testament”), otherwise so quick to didactically point out the transgressions of its characters, remained largely silent on this practice. Silent, that is, when Jehovah was not telling his followers to take on an additional spouse.

Nor did the New Testament, filled as it is with explicit renunciations of many of the strictures laid down in the first half of the book, give me any better handle on this question. When Jesus was asked what would happen to a multiple widow once she reached Heaven, asked to whom would she be married, he gave a sublimely evasive answer: in the afterlife, there is no such thing as marriage.[1] As interpreted by two thousand years of theologians, this verse has come to mean that sexuality will simply be cancelled out in the hereafter.[2]

This notion, to my teenaged self, was less than satisfying, as was another fact that became more visible as I encountered feminist ideas: those men of the Bible had two, three, even three hundred wives, but the women enjoyed none of the same privileges. That hardly seemed fair. It was only when I actually fell in love, though, that any of these ideas started seeming like questions that demanded answers, and not in some abstract, theological hand-waving sort of way.

Lost in the Love Triangle—The Human Capacity to Love Freely

I started dating seriously at nineteen, somewhat late in life to judge by my peers. I’d been in love before that, a series of near-misses and one-sided attractions that ran the gamut from crushes to deep-seated infatuations. The complexity of a reciprocated love, however, was far more beautiful, intense, even painful, than those earlier experiences. My girlfriend, whom I had known, respected, and desired for years, was the world to me.

I started dating seriously at nineteen, somewhat late in life to judge by my peers. I’d been in love before that, a series of near-misses and one-sided attractions that ran the gamut from crushes to deep-seated infatuations. The complexity of a reciprocated love, however, was far more beautiful, intense, even painful, than those earlier experiences. My girlfriend, whom I had known, respected, and desired for years, was the world to me.

What surprised me over the ten months we dated, what made me question the reality of the feelings I had for her, was this: despite all the love and desire I had for her, I didn’t stop loving another of my friends (one of those one-sided situations). I knew, of course, that a monogamous relationship does not erase sexual attraction to others. After all, even by then (the late nineties), the divorce rate had reached levels that would have horrified most any previous generation, and I knew quite well that many of those marriages had dissolved because one spouse had fallen for another person. But I’d always had the idea that these things happened in, you know, an orderly fashion. You love A; you meet B; you start loving B; you stop loving A. A simply syllogism, one supported by centuries of romantic stories, inane love songs, and that most insidious form of societal control, folk wisdom. Loving two people meant, at best, you were at a crossroads, forced to choose between good-enough and best (to employ the logic of most love-triangle narratives). At worst, it meant you were a cad or a player (if you were a man), incapable of settling down into a “serious relationship.” And if you were a woman … well, the words used for a woman who couldn’t confine herself to one lover left little to the moral imagination.

Yet here I was, loving two. And why not? Why was exclusivity reserved for this one experience of love and no other? Any parent who told you that they loved their first child all the way up until the second was born would strike you as inhuman (or at least embarrassingly candid). Any good friend who told you that they had, alas, met a new friend and would no longer be able to accommodate the feelings they’d had for you would seem strange, even brutal.

Nor is the human capacity to love freely restricted to relationships. Loving multiple authors, musicians, political heroes, regions, cuisines, and hobbies is so far from controversial that it may be considered the rule. Anyone who fixates on only one of the above (loving sushi, for instance, and forsaking all other edibles) generally comes across as a bit weird, in need of some world-expanding. So what is it about erotic passion that demands one channel it into a single stream? The more books I read on anthropology and history, the more I understood about the family of primates to which human beings belong, the more I saw that monogamy is a cultural institution. Much like the assumption that heterosexuality is the only acceptable sexual orientation (a concept termed “heteronormativity”), monogamy has been upheld as the only avenue that “real” love walks. This idea is pressed on us from so many directions that it ceases to look like ideology and instead takes on the appearance of nature.

The Jealousy Instinct—Hunting the Wild Wibble

But what about sexual jealousy? Jealousy is so powerful it has led to wars. It lurks behind many abusive relationships. It is the cause of more heartbreaks than can be imagined. Surely, the very ubiquity of jealousy tells us that monogamy is natural. Well, no. Ignoring, for the moment, the rarity of sexual monogamy in the animal kingdom (and its almost complete absence in our closest animal kin), one needs only to ask: do we really want to make instinctive reactions our moral benchmark? Violence comes all too naturally to plenty of human beings, as do laziness, narcissism, and narrowness of mind. Jealousy, as I came to understand through my own reactions, may be “natural,” but that says nothing useful about what to do with it. And monogamy, despite this fallacious “appeal to nature,” does not actually eliminate sexual jealousy. It may, in fact, exacerbate it.

Columnist Dan Savage sums up his problem with the monogamous ideal in his typically direct and amusing style:

“My problem is, we’re told that if we’re in love, we won’t want to sleep with anybody else. The truth is, if we’re in love and we make a monogamous commitment, that means we will refrain from sleeping with other people. We still want to sleep with other people.”

For the monogamous, this desire is a problem, one which needs to be discussed, negotiated, repressed, or dealt with in some other way (healthy or not). For polyamorists, sexual jealousy holds roughly the same position. There is a misperception that polyamorous people don’t feel jealousy. This is an entirely understandable mistake, as polyamorists usually try their best to restrict the power they give this feeling. If your idea of erotic love has been entirely associated with sexual exclusivity, an encounter with someone whose lover has other lovers may easily lead you to assume that this is a very strange person, a person who doesn’t feel the same insecurities, anxieties, and other unhappy feelings you may feel when contemplating your own lover sleeping with someone else. In truth, we often do. There’s even a word polyamorists have coined to describe small bursts of jealousy: wibbles. The question is what to do with your wibbles.

A surprising amount of sexual jealousy can be dealt with by simply being honest about what one feels. Jealousy feeds on secrecy, on lies and evasions and every other trick of dissimulation. “Does my lover want that new work colleague? Is my lover falling for that close friend?” When you can be honest about your desires, and when their expression need not spell an extinction-level event for your relationship (to borrow another of Savage’s phrases), they are often far less damaging than they might have been otherwise.

Polyamorists generally (though not always) introduce their lovers to one another. This connection, between two people who are sleeping with a third, is so foreign to normative relationships that yet another word has been invented to describe it. The lover of your lover is your “metamour,” a coinage derived from the term “paramour.” Meeting your metamour is another experience that can temper, if not erase, jealousy. It can also lead to friendships, new sexual relationships, and some of the strangest Thanksgiving dinners one can imagine. Most powerfully, though, jealousy can be met by a counteracting force of sympathetic joy. Contrary to everything we are still taught about erotic love, people can feel pleasure that their partner is spending time with someone who makes them happy. This is another one of those things that makes perfect sense to most people until orgasms are involved. Polyamorists tend to refer to this feeling as “compersion,” and while it takes some getting used to, while it is just as fragile as any other constructive emotion, it can come to be as natural a reaction as jealousy.

The Cuckold/Sleazeball and the Free Fuck—Polyamorous Stigmas and Stereotypes

After my first relationship died, I began wondering if I could do it differently the next time. When I began dating my wife, I decided to be honest about my doubts regarding the need for sexual exclusivity. I found, to my surprise and happiness, she was thinking along the same lines. What was at first an “experiment” has developed into a fifteen-year relationship. It may have helped that we did have these conversations very early in our connection. As our love for one another developed from early excitement into love and an abiding commitment to one another, so did our ideas of how to negotiate non-monogamy in a thoughtful, caring, and (importantly) fun way.

When we started, we didn’t even have a word for what we were doing. The word “polyamory” had only been coined a few years before this and had had little time in which to percolate throughout culture. We met some pushback along the way, and not all of it from expected sources. Some cultural conservatives, for instance, showed a shocking amount of tolerance for what we were doing, while some otherwise liberal folk saw fit to lecture us about the obviously transitory and idealistic nature of our relationship. Those who belonged to the latter category often conflated polyamory with the sort of predatory polygamy practiced by some reactionary groups. That we still sometimes encounter this sort of mistake is befuddling. Polyamory, like any other healthy relational structure, is meant to be practiced by consenting adults.

Many of the problems polyamorists are likely to meet come not from the internal stresses and complications a branched relational structure can produce, but from the society around them. Despite the spread of polyamorist ideas, monogamy is still the dominant narrative. Being a polyamorist can be quite lonely when you cannot find like-minded people, a situation exacerbated by the fact that the movement is not characterized by recognizable social cues. Your chances of correctly identifying a polyamorist in a party or across a crowded bar are virtually nil.

When non-monogamists are represented in the media, they are usually depicted as predators, heartless hedonists, or, at best, laughable idealists. And interactions with people who don’t understand (or accept as valid) the nature of polyamory can be even more painful. Heterosexual polyamorist women, for instance, are sometimes treated like a “free fuck,” particularly by otherwise monogamous men who jump at the chance to sleep with women they feel no obligation to show any real care for. If, on the other hand, a polyamorous woman wants an encounter with minimal strings attached (plenty of polyamorists enjoy casual sex as much as monogamists), she may find herself under depressingly familiar slut-shaming judgments with an added layer of opprobrium because, after all, she is “straying” from another relationship.

Polyamorous men, on the other hand, are faced with what one might call the Cuckold-Sleazeball dichotomy. On one side, the straight/bisexual man who “lets” his partner sleep with other men is often viewed as a sad, if not funny, figure. On the other, men who look for or are open to additional relationships are often seen as predatory figures, jerks who’ve somehow pressured their partners into the lifestyle, creeps determined to leverage their philosophy into as many fucks as they can manage.

As dire as this sounds, however, many of the difficulties polyamorists must navigate are more subtle. Most are directly linked to a lack of community and to an invisibility still produced by the dominant monogamous narrative. Over the years, I found that people such as my wife and I have always existed. In his poem Epipsychidion, for instance, Percy Bysshe Shelley declares that he “never was attached to that great sect, / Whose doctrine is, that each one should select / Out of the crowd a mistress or a friend, / And all the rest, though fair and wise, commend / To cold oblivion” (149-153).

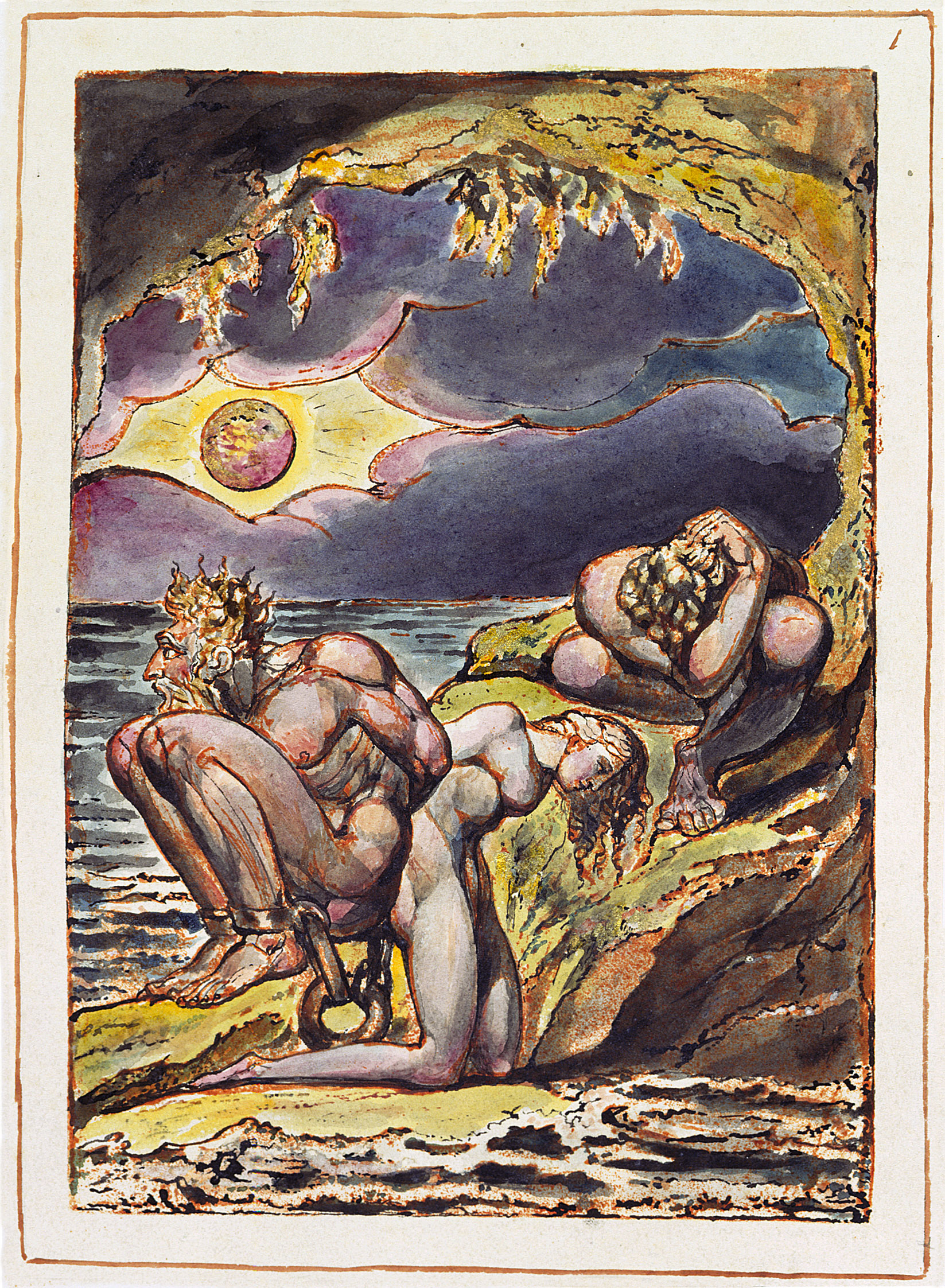

William Blake saw in “free love” a power, possibly the only power, capable of breaking the stranglehold oppressive ideologies have on society. He sets forth this idea most clearly in Visions of the Daughters of Albion, in which he describes sexual jealousy as “a creeping skeleton / With lamplike eyes watching around the frozen marriage bed” (195-196). These proto-polyamorists sought a love that rejects sexual exclusion and possessiveness, but were met with religious obstructions and social disapproval. Only recently has their ideal become possible outside the confines of secret societies and isolated communes such as the Oneida Community.

Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Amelia Earhart, Anaïs Nin, Henry Miller, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, Warren Buffett, Margaret Cho, Neil Gaiman, Amanda Palmer, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee are only a handful of those who have negotiated or continue to negotiate polyamorous relationships. This is, however, a history which remains to be written. Most polyamorists would be at a loss if asked to name a single precursor in history, and that invisibility does little to help them feel like a part of the social web. It reinforces the idea that their love is only an experiment, the sort of thing people played at during the Sexual Revolution only to set aside as fundamentally unworkable. This is simply untrue. In plenty of cultures around the world, monogamy is far from compulsory. And I haven’t even touched on those people who, try as they may, seem incapable of staying monogamous in relationships.

Orientation, Exclusion and Other Polyamorous Problems

A consideration of the latter brings up a question even polyamorists cannot agree on. I have, for years, seen some inveterate cheaters as closeted polyamorists. While some people stray from monogamous fidelity out of reasons more or less disconnected from love, plenty of others do so because they genuinely find themselves attached to more than one person. Our society still characterizes this as a failure: a failure to settle down, to engage in “serious” relationships. Rather than be honest with themselves about their needs, they end up in one doomed situation after another, damning themselves as “unfaithful” all the while wounding partners who had expected something else.

I’ve met people who, after years of this sort of disappointment, decided that the problem was not them, nor was it the partners they had hurt along the way. The problem was, instead, the mold into which they had forced themselves to fit, an ideal for which they were not suited. The comparison with the experience of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people seems inevitable. Yet this idea, that polyamory may be an orientation, is something polyamorists are split over. Some see it as a choice, while others feel that any other way of loving (namely monogamy) would be alien to them (or at least extremely unrewarding). Many monogamists, even those who would consciously reject polyamory as an orientation, echo this idea. If there is a phrase I’ve heard more than any other in response to my lifestyle, it is some variation of: That’s great if that works for you, but I could never do that. Is this because they are just inherently monogamous? The question may seem academic, but it has relevance in a world in which monogamy is still typically understood as not only the norm, but also as really the only game in town. The question also matters in that polyamorists currently enjoy very little in the way of legal protection, and have lost jobs and even custody of their children because they are often portrayed as deviants.

The polyamory community, such as it is, has its own internal struggles. Polyamorists tend to skew left, and most practitioners are committed to egalitarian ideals. Poly meet-up groups often open with an invitation for members to share their orientation, should they wish to, as well as an encouragement to state their preferred pronouns. Still, many queer people find themselves treated differently than their straight poly-comrades. Gay/bisexual men and trans individuals may encounter the same sort of exclusionary tactics they might expect from heteronormative sub-cultures, while bisexual women, for instance, are sometimes fetishized. There is nothing wrong with threesomes (either sexual or relational) involving two women and one man (assuming, of course, all the parties consent to the arrangement), but the popularity of this configuration can sometimes mimic broader patriarchal trends. The so-called “one dick rule,” wherein only new women are allowed into the relationship, may be something a couple chooses for perfectly valid reasons, but it is often adopted for less than admirable reasons.

Also, despite the generally progressive tendencies of polyamorists, people of color sometimes report feeling ostracized within these groups; that or approached like they are exotic treats instead of individuals with needs of their own. These problems are not, of course, unique to the world of polyamorists. The intersection between sexual and racial identities has a long and ugly history, particularly in the United States, and has left scars on the body politic that must not be ignored. Neither can the legacy of misogyny be simply wished away. My hope is that polyamorists may, in our own small way, help heal these rifts by modeling behaviors of inclusiveness, self-awareness, and honesty.

Stretching the Emotional Imagination

The latter is, after all, what polyamory is about. My partner and I have learned that non-monogamy requires being as open as possible with one another. Sometimes you have to risk hurting each other rather than ignoring an issue. Often, you come face-to-face with insecurities and limitations within yourself of which you were not aware. If you can’t have adult discussions about your feelings and those of your partners, you will probably find polyamory difficult. You will also, I imagine, find monogamy troublesome.

The latter is, after all, what polyamory is about. My partner and I have learned that non-monogamy requires being as open as possible with one another. Sometimes you have to risk hurting each other rather than ignoring an issue. Often, you come face-to-face with insecurities and limitations within yourself of which you were not aware. If you can’t have adult discussions about your feelings and those of your partners, you will probably find polyamory difficult. You will also, I imagine, find monogamy troublesome.

Polyamory does come with some unique opportunities to stretch your emotional and relational imagination.[3] Rules, for instance, are something you have to consider. Does your relationship need them? Should you introduce any potential lovers to your partner before sleeping with them? Do you have “veto power” over any particularly obnoxious new addition to the relationship, or is such a rule too restrictive? How are you going to schedule time with your partners in such a way as not to shortchange any of them? Is there a sexual position you reserve for use with one person? Who gets to be the “plus one” at a wedding? The upside to all this is that it is usually much more fun than it might sound. Vulnerability and straightforwardness are certainly scary, particularly in a society that still treats romance as being dependant on mystery and implication. But that openness can lead to deep intimacy and trust.

Being polyamorous does not mean, as that old bit of seventies schmaltz would have it, “never having to say you’re sorry.” You will, most likely, have to say sorry quite a few times as you negotiate the borders and rules of your relationship. It does mean, however, not having to hide quite natural desires from one another out of the fear of transgressing a limitation of strict sexual fidelity more and more people are coming to see as arbitrary. This, in itself, can add erotic frisson to your relationship. Knowing your partners desire and are desirable people needs not be a traumatizing experience, as monogamy trains us to think such a revelation must be. It can, instead, remind you of just how lucky you are to be a part of this sexy person’s life. Time is a limited quantity, certainly, but in my experience love is not a zero-sum game. As Shelley puts it:

“True love has this, different from gold and clay, / That to divide is not to take away. / Love is like understanding, that grows bright, / Gazing on many truths” (160-163).

When you leave yourself open to passion and intimacy and extend to your partners the same courtesy, you may find your capacity to care and desire grow beyond what you thought possible.

[1] Matthew 22:23-30

[2] The notion that sex will be freed of all constraints after death, that Heaven will be, among other things, a never-ending metaphysical orgy, has to my knowledge rarely been proposed. This, surely, one of the great missed opportunities in religious public relations.

[3] Yes, I am aware this is pitch language.

Suggested Reading

Opening Up – Tristan Taormino

The Ethical Slut – Dossie Easton and Janet Hardy

Polyamory: The New Love Without Limits – Deborah Anapol

Matthew Pridham writes horror fiction. He is soon to enter CU Boulder’s MFA program, after having earned his Master’s there. His novella Renovations was published in Weird Tales, his essays on strange films have found their way onto Weird Fiction Review and he is currently wondering if a story has ever been told entirely in the form of authorial bios.

Matthew Pridham writes horror fiction. He is soon to enter CU Boulder’s MFA program, after having earned his Master’s there. His novella Renovations was published in Weird Tales, his essays on strange films have found their way onto Weird Fiction Review and he is currently wondering if a story has ever been told entirely in the form of authorial bios.

4 thoughts on “To Divide is Not to Take Away: My Life as a Polyamorist”