by Melissa Brooks

When I was a little kid, I didn’t understand the role periods played in reproduction. I didn’t know sex had anything to do with penetration. My understanding was only that it involved two people rolling around together, kissing and moaning, and that it was a cardinal sin unless it occurred between a husband and a wife in the privacy of their bedroom.

Knowing little about the subject aside from it displeasing God, sex scared me. At slumber parties, my prude hands wanted to cover my prude ears as friends exchanged stories about boyfriends and girlfriends undressing each other or stories with a punch line: A little boy points at his mom’s breasts and asks what they are. “Those are my headlights, honey.” He asks what her mound of pubic hair is and she responds, “That’s my bush.” Dad’s penis? “That’s my snake, son.” That night he asks to sleep in his parents’ bed and they say yes, as long as he doesn’t look under the covers. But he peeks anyway and shouts, “Mom, quick! Turn on your headlights! Daddy’s snake is slithering into your bush!” Hearing these stories felt tantamount to performing the vile acts they described. I feared eternal damnation was imminent.

The fear was compounded when I saw sex visually manifested in movies and on television. I saw Titanic for the first time when I was nine in a crowded theater with my mother. As Rose dropped her robe to pose for Jack, I was horrified to see her swelling breasts and even more horrified to be sitting next to my mother, as though I was doing something wrong; never mind she was the one who took me to this movie. Was everyone in the theater as uncomfortable as I was as Rose glided to the chaise and laid back? Did everyone else feel the urge to break free of their skin and burrow into a hole? Was everyone else’s laughter tainted with nervous anxiety when Rose made a pouty face and mocked Jack, “So serious”? Even Jack trembled in her presence, her naked body evoking power, instilling fear.

It was worse when I saw The Shining. A bathroom. Sea foam green with bright yellow trim. It appears empty but then a wet, naked woman pushes back the shower curtain. She stands slowly to reveal a slim body and firm breasts. Just as slowly, she walks toward Mr. Jack Torrance. Her wet, slicked back hair is unflattering but still, Jack welcomes her lips.

Ten years old, sitting in my sort-of friend’s basement, shock bombarded me: the woman’s full frontal nudity; total strangers kissing without hesitation despite not speaking one word to each other, despite one of them being married; my friend informing me that men are powerless in the presence of the naked female body: “But he’s married!” “So? You really think he’s not going to kiss a naked woman?”

The shock turns to horror as her skin rots off and she transforms into an old, diseased, maniacal woman—mingling my fears of death and sex together to create the most horrifying scene of my childhood. I still wake up in the middle of the night picturing that rotting old woman rising from the bathtub.

And it’s no small coincidence[1] that the only images of nudity in film I remember seeing in my childhood were mingled with such horror. Not long after Rose poses nude and has sex with Jack, the Titanic strikes the iceberg, leaving the gargantuan vessel broken, slowly sinking while thousands drowned or froze in agony. And soon after Jack Torrance kisses the naked, rotting woman, he tries to kill his family. Conclusion: Sex = horror. Sex = destruction.

This belief was reinforced when I first watched Scream and Randy repeated the mantra, “Virgins never die.” Translation: sex kills. Never mind Sydney didn’t die after she asked Billy if he’d settle for a PG-13 relationship and flashed him, after she asked why her life couldn’t be a good old-fashioned porno, or after revealing her bare back as she removed her bra, Billy moving toward her entranced by presumably powerful breasts. All that mattered: she had to run from a murderous boyfriend and watch her friends die.

When I acquired my first “real” boyfriend freshman year of high school—the first boyfriend that actually spoke to me, rather than just shyly passing notes; the first boyfriend who spent any time with me; the first boyfriend who kissed me—he repeatedly tried to stick his hand beneath my shirt and I felt like I was in one of those television shows of the 90s that so often served as PSAs. [2] Understanding that sex equaled bad things, I always pushed his hand away. Every time, he gave me a hurt look and sulked so that I started to feel bad. And after a month or two, I grew weary and demoralized and finally let him touch me.

In my young teenage mind, I buried the images of rotting women; dissociated sex with sinking ships, frozen lovers and sociopathic serial killers. I had to as I gave that hand free range to wander from the caverns of my shirt to my underwear. To live, you must willfully forget that you’re going to die, and you must willfully forget that you’re going to Hell.

My mind compartmentalized my long-held beliefs about sex and sin to accommodate my discrepant behavior. I had given into sexual temptation almost the first time it presented itself to me. And I enjoyed it. A lot. I wanted to keep fooling around in his dank basement beneath a dank sleeping bag unzipped to mock a blanket. I had to write myself a new narrative to live my life without fearing eternal damnation and without hating myself for being weak-willed, for compromising my integrity for a boy I didn’t even like that much to begin with, but whose attention I reveled in.

And so I dredged up something else from those films of my youth—the idea that the naked female body is inordinately powerful. Men would succumb to it. Tremble beneath it. Like Rose DeWitt Bukater, the nameless bathroom woman and Sydney Prescott, I could instill desire or fear. I would be in control. I would come out on top—their men not only crumbled in their presence, they all died; Jack Dawson and Jack Torrance froze to death while Billy Loomis’ organs failed him after multiple gunshot wounds (inflicted by women, nonetheless). Instead of fearing sex, instead of fearing damnation, I would choose to revel in my power every time I let him touch me.

About eight months in, our relationship took a sour turn. He became mean. Yelled at me for throwing banana peels in the wrong garbage can. For accidentally bumping some elusive “cyst” when I hugged him. Whipped a soccer ball at me as hard as he could. Suddenly, I was the one trying to propel our physical relationship forward. Encouraging him to buy condoms so we could at last “go all the way.” Convinced that I could heal this crumbling romance with the power of my body. And he spurned me.

It made me feel pretty bad, disgusting, even, believing as I did that the female body is an all-powerful weapon and yet, it failed to get me what I wanted; believing that men become instantly aroused and helpless at the site of it and yet, a man rejected mine.

It became a pattern for a while as I repeatedly tried to salvage fragile relationships with sex—and in turn justify spurning my beliefs so it hadn’t all been in vain. Thankfully, I grew up and stopped treating sex like a handy trick. Realized that men are not powerless in the presence of nudity and value more in a relationship than sex. Realized that my first boyfriend was an immature and manipulative jerk. Realized that sex will not be my destruction so I need not validate the choices of my youth. And lastly, realized the impressions movie sex made on me as a kid were merely that—impressions, neither factual nor universal.

[1] Team Elaine Benes all the way—of course there are degrees of coincidences.

[2] Re: 7th Heaven, Full House, Step by Step, Sabrina the Teenage Witch, et al.

Melissa Brooks is Assistant Editor at The Thought Erotic. Her fiction and cultural criticism has appeared or is forthcoming in Gravel, Vannevar, The Molotov Cocktail and Saturday Night Reader.

Melissa Brooks is Assistant Editor at The Thought Erotic. Her fiction and cultural criticism has appeared or is forthcoming in Gravel, Vannevar, The Molotov Cocktail and Saturday Night Reader.

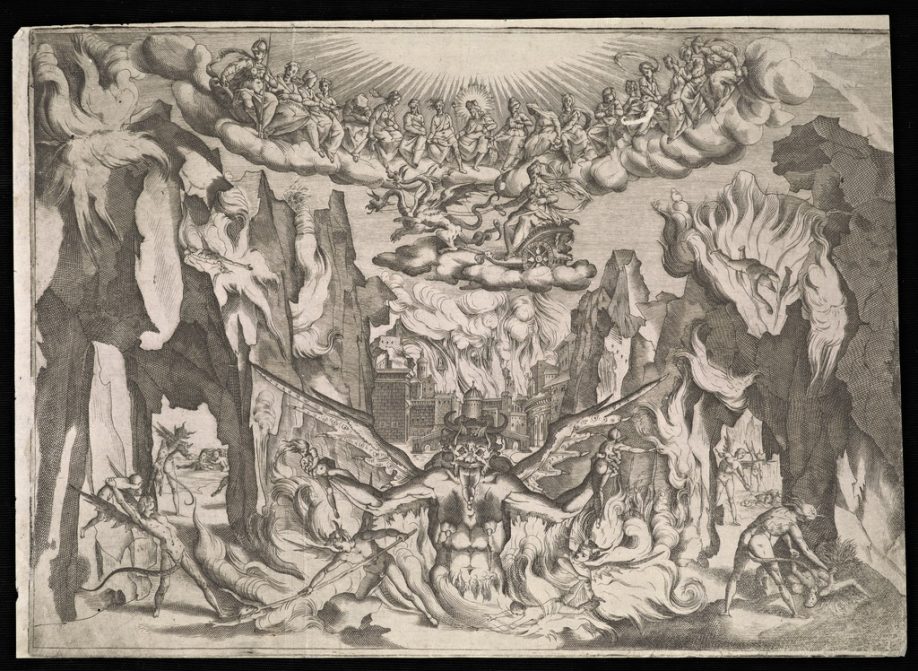

Image: Epifanio d’ Alfiano, “Hell,” Courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program

2 thoughts on “Escaping Hell: Sexual Horror in Titanic, The Shining & Scream”