Princesses, Prostitutes, Penises and Patriarchy—What Pretty Woman and The Little Mermaid Taught Me About Sex, Bodies and Womanhood

by Courtney Morgan

Edward: Tell me, what kind of money do you girls make these days, ballpark?

Vivian: Can’t take less than a hundred dollars.

Edward: Hundred dollars a night?

Vivian: One hour.

Edward: An hour? You make a hundred dollars an hour and you’ve got a safety pin holding your boot up? You’ve got to be joking.

Vivian: I never joke about money.

Edward: (Laughing) Neither do I. A hundred dollars an hour. Pretty stiff.

Vivian: (Reaches into his lap) Well, no, but it’s got potential.

(Zoom out to a 1990s rec room basement, four adults and two children scattered across couches and rugs. A woman grabs the remote. Vivian and Richard freeze on the screen.)

This is the point where my uncle breaks into the story heretofore occupied only by Julia Roberts and Richard Gere, and explains Vivian/Julia Robert’s “potential” comment to my mother; I’m seven years old, sitting across the room from him, horrified. (Why he had to explain this to my mom is still the inexplicable part—was someone talking, did she miss what JR said, did she not get the reference, did she not understand erections? Did no one see the seven year old?! Too many questions. What I do know: Richard Gere and boners took on a low-boil level of terror, fascination and creepiness. Essentially, they were both ruined.)

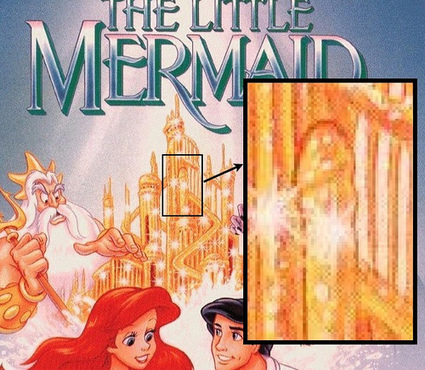

(Cut to the same rec room, now occupied by three young girls, arranged across each other, legs entwined on the navy polyester couches, a white plastic bubbled VHS case gripped tightly by several hands, wrestled back and forth between their faces—held close the noses and then at arms length. One girl holds a remote control in her hand. On the screen, frozen into timelessness is a cartoon wedding scene, a miniaturized priest presiding in an over-sized mitre, a small but identifiable lump protruding from his waist.)

Growing up with all sisters, I wasn’t as a child exposed to a lot of phallus, plain and simple.[1] A couple of months before Uncle Bob’s intro-to-boners chat during Pretty Woman, The Little Mermaid and the golden age of Disney had burst into my second-grade life. It wasn’t until about a year later that the scandal about the penis castle tower and the priest with the boner caught on, but I remember the fervor with which we reacted, poring over the VHS cover with my girlfriends, none of us really sure which spire it was (I mean, really, how many spires aren’t phallic), and pausing and rewinding the wedding scene over and over, giggling and gagging about male genitals.

It’s interesting in hindsight that I was exposed to Pretty Woman and The Little Mermaid during pretty much the same time period, because now it feels like two different girls who watched those movies. There was the seven year old who adored cartoons and fairy tales (though I was never much impressed by princesses and found Ariel’s thirst for adventure much more enchanting than her dresses[2] or entanglement with Eric). And then there was the girl, who even at seven was beginning to understand and prepare for womanhood, for puberty and the dawning of romantic and sexual urges I felt glimmers of even then.

Those two movies, maybe more than anything else I can think of from that time, began to delineate the line between childhood and adolescence, functioned like the perforated line along which my self would tear, leaving the child me behind as I moved forward into my teens, and, into my sexuality.

But what’s most fascinating to me now about these two films—looking at them in the present through a very different lens—is their similarities. (Moving beyond the fact that both protagonists are redheads and neither of them know how to use forks.) Of course, some of the parallels make sense: Pretty Woman co-opts the fairy tale narrative—the prince on the white horse (or white limo) who rescues his trapped princess from the perils of captivity (a jealous stepmother, an overbearing father, spells and magic, prostitution?). But then there are other correlations, which depart from the fairy tale formula (or at least its modern iterations).

Rescue Narratives

As in all fairy tales, the female protagonists need to be rescued. But these films deviate from the classic narrative in that both Ariel and Vivian perform a sort of rescue of themselves first, before the final, typical heteronormative/male rescue story at the end of each movie. (Neither of these self-rescues are without problem or ultimately successful, but the reasons for their failures seem to point back to the patriarchal norms they are attempting to defy, rather than their own weaknesses or inabilities.)

Ariel takes matters into her own hands and enlists the aid of Ursula the sea witch[3] to get where and what she wants. (Not to mention that she saves Prince Eric, twice before he rescues her at the end.) That Ariel has to trade her voice in exchange for legs, and use her sexuality (a kiss) to ensure her escape are points of note that we’ll explore later in the essay.

Vivian, meanwhile, has escaped the prison of small town life and (perhaps?) an abusive home. It’s certainly arguable that she’s trapped in prostitution (like Ariel, her escape is ultimately a failure), but it’s also true that she has created an independent and self-sufficient life for herself; she evades pimps and retains control over her decisions (“We say who, we say what, we say how much”).

According to Debra Satz in “Markets in Women’s Sexual Labor,” if it is possible for prostitution to be free of degradation and inequality, several conditions must be maintained for sex workers, including the freedom to refuse to give sex, having access to adequate information before consenting to sexual acts, the prohibition of outside brokerage, and providing her with other life (social and economic) options (84-85). Clearly Vivian’s circumstances do not meet all of these standards (particularly other life opportunities)—nonetheless, I maintain that her prostitution is an attempt (within a problematic system) at agency and self-representation.[4] But like Ariel, it fails because it doesn’t fit and maintain proper female roles.

I don’t think it was until college that I looked at Pretty Woman a little more critically, when I began to question both the glorification of prostitution and the rich prince rescue narrative. And it wasn’t until even more recently that I began to also question the condemnation of the prostitute: the story that she needs to be rescued, and the gloss-over of the patriarchal systems that create, justify and use both her position as prostitute and the need to ostracize her as such. I did, however, even at seven, appreciate Ariel’s passion and drive, even as it frightened me that she disobeyed her father and trusted the clear villain.

Part of That World

Second connection? Both Ariel and Vivian are “punished” in varying ways for their perceived wantonness, for overt display of their sexuality. Come on, clearly Ariel’s wish to become human, her desire for legs is a coded story about her burgeoning sexual desires (“Betcha on land, they understand, bet they don’t reprimand their daughters. Bright young women, sick of swimming, ready to stand”).[5] Ariel escapes her father’s rule by escaping his domain—but she pays the price. She’s turned into a seaweed creature, and then, in the final betrayal, her father and his dominion of the entire ocean are sacrificed in her place. (Lesson learned, young ladies? Your promiscuity will bring shame and ruin on your entire household.)

Vivian’s use of sex as commerce undermines the emphasized femininity[6] of patriarchal norms—prostitution being a really interesting site where patriarchy folds in over itself in a sense: on one hand it defies the socially reinforced institutions of marriage and monogamy, and gives women a form of control and ownership over their own bodies (excluding, of course, the pimp configuration, which is one way patriarchy can regain control of “loose” women; shame and cultural ostracization being another), while at the same time reinforcing male domination and access to women’s bodies and sexualities as commodities. This display of her sexuality, however, leaves her open to abuse (Scully hits her across the face) and even death (as we see in the “Skinny Marie” prostitute character found murdered in the opening scenes of the film).

Forbidden Fantasy

Then, they’re both stories about transgressive sexuality. The Little Mermaid can be read through a transgender lens;[7] Ariel feels a dissonance between her biological body and her internal identity and desires. “A transgender criticism… looks at stories that do not ostensibly seem to be about embodied gender identity and argues that within those narratives, the mermaid is performing a transgender identity, an identity other than that which is socially assumed or assigned for her character” (Spencer, 113). Ariel subverts social norms and follows her desires and inclinations, regardless of whether they were deemed perverse, dangerous or wrong (“Contact between the humans and the merworld is strictly forbidden. You know it, everyone knows it.” Triton tells her. “Have you lost your senses completely? He’s a human; you’re a mermaid!”).

Returning to my own experience for a moment, while I didn’t recognize Ariel’s desires themselves taboo as a child, I do remember Ariel as one of my first childhood “girl crushes,” and I now recognize how those sensations opened up an unspoken rift in myself—between what I had seen and been told I would feel when I felt those first fleeting stirrings of romance (sexual desire) and what I was actually feeling, which was far more interested in Ariel and her seashells than Eric. I didn’t have language for it, but I did sense the split, which began to destabilize the heteronormative narrative as what everyone without question/exception will and must follow and fit because it’s natural and normal and good.

Vivian’s transgression is obvious—prostitutes are transgressive, sex for sale is deviant (and criminalized as such).

There’s also the way Vivian crosses the class divide, which could be transgressive, but is ultimately rendered acceptable by the story. Yes, classism is rampant and unexamined in Pretty Woman, and although the social climbing is frowned upon within the film, the takeaway message for women is clear: if you’re pretty enough, it doesn’t matter if you’re uneducated, desperate and poor—you can still be a princess; and for men: you can find a woman in poverty, dress her up how you like and tell her what to do—and be a savior.

Happily Ever After: The Final Reinforcement of Patriarchal Norms

But then, of course, all of the transgressions and silly attempts at self-ownership and agency get neatly wrapped up in the ultimate heteronormative, monogamous, patriarchal happy ending.

It’s interesting that Ariel’s trade with Ursula requires first, for her to give up her voice (in exchange for sexuality) (“On land it’s much preferred for ladies not to say a word, it’s she who holds her tongue that gets the man”), and secondly to use her sexuality (“Don’t underestimate the importance of body language”) to win the ability to stay human (a kiss). She needs that first sexual experience to fully transform, to become fully human. And yet, because it’s not within the bounds of patriarchal, heterosexual norms, she ultimately fails (even Ursula slut-shames her when she almost succeeds in kissing Eric in the lagoon: “The little tramp”). As for the exchange—she has to give up ownership of her voice in order to succeed in owning her body/sex. She can be either body or mind, but not both.

As noted, this self-sufficient attempt at claiming her body and sexuality fails. When she finally does kiss Eric—after her father grants her the right to become human—the first kiss transforms into the wedding kiss: patriarchal structures locked neatly back in place, check. With her father’s permission and blessing, she’s finally allowed to transform into a human and own her body and sexuality—provided that it’s with the other man her father has passed her along to[8].

And the grand enforcer of patriarchy—heterosexual monogamous marriage—isn’t only in charge of keeping women in check (those hypersexual hysterics who will run wild if left to their own devices); Eric is subjected to it as well (Grim tells him, “It’s not only me, Eric. The whole kingdom is ready to see you happily settled down).

Vivian, too, is ultimately saved (and held carefully in place) by her “happily ever after” of marriage and monogamy and carefully regulated sex. Safe from the dangers of the street, with no need to return to school in San Francisco or pursue her own goals.

While these films presented my young self with complications to and transgressions of regulated female sexuality, they ultimately reinforced the unspoken narrative of what it means to be a “good” woman. The Little Mermaid and Pretty Woman taught me about male excitory functions and anatomy, but they also taught me about hegemonic patriarchal normalcy, and what exactly it would mean to become a woman.

[1] (A shower scene could go here: me with a male cousin, young enough to still be taking co-ed-cousin showers, being chased around while he pointed his penis squirt-gun style at me and shot me with urine. Pissed that I couldn’t shoot him back. That’s about the extent of my exposure.)

[2] Except those sea shells… But more on that later.

[3] The familiar shunned female figure, exiled from the castle for unknown reasons, though there are implications that it was her raucous behavior (“In MY day; we had fantastical feasts when I lived in the palace”) and her desire for power (along with the fact that she turns merfolk into shivering seaweed creatures to suit her needs).

[4] Elizabeth Bernstein in “What’s Wrong with Prostitution? What’s Right with Sex Work? Comparing Markets in Female Sexual Labor” says, “Prostitution may, nevertheless, be experienced by some of these women as both an economically and sexually liberating option. Given the range of economic and sexual alternatives in a society in which female sexuality is already appropriated, in which rape, incest and forced sex with boyfriends have been the routine litany of their coming of age, prostitution may ironically be the first time that they have experienced the notion of ‘consent’ as at all meaningful.”

[5] I read several articles about the “terrible lessons girls learn” from The Little Mermaid, many of them referring to ignoring and disobeying her father. Other, feminist readings addressed the fact that she gives up everything, her family and home, for a man—which may be valid, but I disagree. She wanted to be human long before she met Eric (her budding sexuality was there, all along); he just became a specific object to direct her affection towards.

[6] R.W. Connell “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.”

[7] For a thorough transgender reading, see Leland G. Spencer’s “Performing Transgender Identity in The Little Mermaid: From Andersen to Disney.”

[8] This doesn’t jive with the earlier mentioned transgender reading, however; through that lens, Triton turning her into a human is a final acceptance of her true identity. Which would be nice. But returning to the reading that Ariel’s humanness is akin to her sexuality, his permission and acceptance is offered within the strict boundaries of heterosexual, patriarchal norms.

Works Cited

Bernstein, Elizabeth. “What’s Wrong with Prostitution? What’s Right with Sex Work? Comparing Markets in Female Sex Labour.” Hasting’s Women Law Journal 10.1 (1999): 91-117. HeinOnline. Web. 9 Mar 2015.

Connell, R.W. and James Messerschmidt. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender and Society 19:6 (Dec 2005): 829-859. Sage. Web. 9 Mar 2015.

Spencer, Leland G. “Performing Transgender Identity in The Little Mermaid: From Andersen to Disney.” Communication Studies 65:1 (2014): 112-127. Radford University. Web. 9 Mar 2015.

Satz, Debra. “Markets in Women’s Sexual Labor.” Ethics 106:1 (Oct 1995): 63-85. Jstor. Web. 9 Mar 2015.

Courtney Morgan is the founder and managing editor of The Thought Erotic. She also writes about sex, culture and all things literary at TTE and Vannevar. Her writing has appeared in Pleiades, The Red Anthology and American Book Review. She is a recipient of the Thompson Award for Western American Writing and was shortlisted for Glimmer Train’s Short Story Award for New Fiction.

Courtney Morgan is the founder and managing editor of The Thought Erotic. She also writes about sex, culture and all things literary at TTE and Vannevar. Her writing has appeared in Pleiades, The Red Anthology and American Book Review. She is a recipient of the Thompson Award for Western American Writing and was shortlisted for Glimmer Train’s Short Story Award for New Fiction.

Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

One thought on “Princesses, Prostitutes, Penises and Patriarchy”