by Melissa Brooks

Part I: Acknowledging your own cissexism

Although transsexuals have long existed, they have not long been at the forefront of public consciousness. While mainstream society is finally beginning to acknowledge and openly discuss trans issues, trans people remain very much marginalized and continue to be persecuted. Most cissexual individuals—those of us whose gender identity matches the one society assigned us—have such a limited understanding of the trans experience because we grew up learning limited definitions of gender, biological sex, sexuality and sexual orientation that fail to account for trans people. As a result, even the best intentioned among us inadvertently harbor cissexist ideas—the belief that transsexual genders are less legitimate than, and mere imitations of, cissexual genders.

* * *

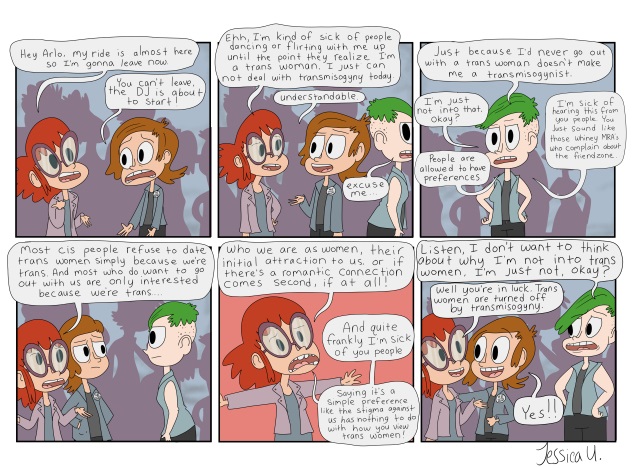

A good friend of mine is married to a woman named Jessica who is trans. Because of this, I used to naively think that I couldn’t possibly be cissexist. As the creator of Manic Pixie Nightmare Girls—a comic shining a spotlight on trans issues while upending hetero-normative, patriarchal ideas that suppress women—Jessica has alternately educated and frustrated me, the latter being those times her comic challenged my self-image as an open-minded, accepting individual.

A strip she shared recently, for example, made me grapple with the possibility that I might be a transmisogynist—someone who discriminates specifically against women who are trans. In a Facebook post, Jessica wrote:

“There is no quicker way to upset cis people (or anyone else who isn’t a trans woman) than to tell them their romantic repulsion towards trans women is linked to transmisogyny. I can’t count the number of times I’ve been pursued by someone up until the moment they found out I’m a woman who is trans … if you’re attracted to women, and if a woman being trans is your one and only deal-breaker, you just might be a transmisogynist.”

I support the rights of trans individuals. Any trans woman should be able to walk into a women’s public restroom without being harassed. To walk to work without some idiot screaming obscenities at her. To go on a date with a man without that man’s friends later making her the butt of their jokes and a constant point of ridicule for years to come.1 Surely, I am not a transmisogynist, I thought. And yet, I was confronted with the idea that I just might be one, because my initial reaction—which not only missed the point, but also reinforced transmisogyny—was that genitalia and sexual orientation go hand in hand.

For a long time, my understanding of gender dissonance was that affected individuals feel trapped in the wrong body. Their internal identity doesn’t mesh with their genitalia. So, while a trans woman is a woman, I couldn’t help but think she was nonetheless a woman in the wrong body if she does not have or has not yet had sex reassignment surgery.2 So I thought it wasn’t really fair to call someone a transmysogist for not wanting to have sex with a woman who is trans (or for defending someone who doesn’t want to have sex with a woman who is trans). If a man is classified as straight because he’s aroused by breasts and vaginas, if a lesbian is defined as such because she’s aroused by the same, are they really to blame if they’re not aroused by a woman with a penis?

Repulsion, of course, is problematic. But I don’t want to have sex with most people—that doesn’t mean I’m repulsed by most people. I’m not. If someone was repulsed by the thought of having sex with a trans woman, that is unequivocally transmisogynist and cissexist.3 But it’s possible for someone to not be aroused by a trans man or woman without repulsion coming into play.

If sexual orientation is inextricably linked to genitalia, the implication is that only bisexuals or people with a trans fetish could be attracted to trans individuals. And yet, if I were to say that only bisexuals or fetishists could be attracted to trans individuals, wouldn’t I be undermining people who are trans? Yes. Because by saying so, I’d be saying that trans women aren’t one hundred percent women. I’d be sanctioning them as women in the mental and emotional sense, but denying them the right to declare themselves women in the physical sense. And that’s wrong. That’s cissexism. Writer, spoken word performer, trans activist and biologist Julia Serano calls it trans-objectification:

“When people reduce trans people to their body parts, the medical procedures they’ve undertaken, or get hung up on, disturbed by, or obsessed over supposed discrepancies that exist between a transsexual’s physical sex and identified gender” (Whipping Girl, 186).

So what now? Defining both gender and sexual orientation by genitalia is what we’re accustomed to, what so many people have been raised to believe is absolute truth. To better understand and embrace the trans experience, both I and other cis folks have to rethink these beliefs. We must acknowledge that our conceptions of both gender and sexual orientation are too narrow. We are too hung up on genitalia.

Part II: Redefining gender

Recently, I read the article, “Quit Projecting Your Desire: On Transphobia, Lust And Gender” by Jetta Rae DoubleCakes that helped me better wrap by head around sexual orientation and start to move past my indoctrinated cissexist views of what it means to be gay or straight as well as what it means to be a man or woman. Jetta Rae wrote:

Recently, I read the article, “Quit Projecting Your Desire: On Transphobia, Lust And Gender” by Jetta Rae DoubleCakes that helped me better wrap by head around sexual orientation and start to move past my indoctrinated cissexist views of what it means to be gay or straight as well as what it means to be a man or woman. Jetta Rae wrote:

“It’s dangerous to be complicit in this effed up society’s idea of ‘vagina = woman’ because if your whole identity as a person is tied to a single aspect of yourself that you didn’t choose, if someone else gets to decide what makes you a woman, then that thing that makes you a woman can be revoked like a learner’s permit at any time.”

That did something to me. I’d been running circles around my brain trying to understand how trans individuals factor into not just the heterosexual, but the homosexual experience. I needed someone else to spell it out for me. I was so hung up on the idea that sexual orientation = genitals. I was so hung up on the idea that trans people are trapped in the wrong body. But the truth is, they aren’t—from what I’ve been told and what I’ve read, this isn’t how trans people feel about themselves. Where did I even get that idea? Did I make it up? Did I read it on Wikipedia or WebMD? Is it an idea that many people push but fails to accurately encompass the lived trans experience?

Here’s an idea: Maybe a trans woman’s body is just as female as mine regardless of whether or not she’s had surgery.

Serano says that biologically, this isn’t necessarily a stretch because “man” and “woman” should not be mutually exclusively designations. In her book Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, Serano writes: “The very idea that there are ‘opposite’ sexes unnecessarily polarizes women and men; it isolates us from one another and exaggerates our differences … many people have exceptional sex characteristics and gender inclinations” (103).

Defining men and women exclusively by genitalia—or even by sex chromosomes and reproductive organs—fails to account for intersex individuals, whose reproductive or sexual anatomy demonstrates that male and female are not mutually exclusive categories. It ignores that all people have both testosterone and estrogen in their bodies and “denies the reality that every single day, we classify each person we see as either female or male based on a small number of visual cues and a ton of assumptions” (Serano, Whipping Girl, 51).

Many trans people rightly view themselves as always having been the gender they identify with—they were not born the “wrong gender,” rather, doctors assigned them the wrong gender at birth while puberty unleashed the wrong set of hormones. This seems to be the widely accepted understanding in the trans community. Serano writes:

“Saying that I ‘wished’ or ‘wanted’ to be a girl erases how much being female made sense to me, how it felt right on the deepest, most profound level of my being … my brain expects my body to be female. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that our brains have an intrinsic understanding of what sex our bodies should be” (80).

It’s time to take a step back and ask ourselves why we struggle to accept trans women as one hundred percent women. Why some of us might be ready to accept a trans woman’s feminine identity but, as Serano says, “adamantly draw the line when it comes to accepting [the] transsexual body” (91). Why shouldn’t a woman have a penis?4 Why should her genitals alone define her? Why should anyone’s genitals define them?

Learning to accept a trans woman’s body as authentically female and overcoming the notion that sex=genitals can be liberating for all of us. It means that we cissexual individuals can also stop defining ourselves by our genitals, and what a refreshing idea. As Jetta Rae said: “You are more than your cock. You are more than your vagina. Your body is not the best or worst thing about you … Only you get to decide what makes you a man … what makes [you] a woman.”

Let’s stop allowing other people to define our gender, our sexual orientation, our identity for us. Does this mean that the definition of a woman and man may differ from person to person? Yes. Is that chaotic? Yes. But the existence of trans people proves that our attempt to classify people into two different camps is erroneous. Mentally and biologically, people are complicated and dynamic. It’s naïve to think that just two categories ascribed with a very narrow set of characteristics could possibly classify all people. It’s harmful to rigidly adhere to those categories and to persecute anyone who doesn’t conform.

Part III: How the trans experience impacts your sexual orientation

Now that we’ve addressed our (my) misplaced hang up with genitalia, let’s return to Jessica’s assertion that individuals who are attracted to women might be transmysogist if a woman being trans is their one and only deal breaker.

Now that we’ve addressed our (my) misplaced hang up with genitalia, let’s return to Jessica’s assertion that individuals who are attracted to women might be transmysogist if a woman being trans is their one and only deal breaker.

In her article, Jetta Rae also wrote: “If you’re out at a club or a bar and a woman’s getting your dick hard, it’s not what’s between her legs that’s doing it for you. It’s how she carries herself, how she talks, how she moves—the pussy or cock is all in your mind at that point. It doesn’t exist in that scenario because it hasn’t been observed.”

Often, you have to hear an idea over and over again told in different ways for it to really sink in. Because this (I think) is exactly what Jessica was getting at in her Facebook post and what I was overlooking—sexual interest precedes nudity. Maybe I would have thought about this sooner if I read her strip before getting so hung up on her Facebook post and allowing my fear of being a transmisogynist to eclipse actually listening to what she was saying—because she wasn’t really saying that not wanting to have sex with a particular person makes you a transmisogynist. But rather, if you really dig someone up until the moment you find out they happen to be trans, then you might be.

In the aforementioned comic strip, two women are on a date. One woman says to the other, “This has been the best first date I’ve been on in a long while. And I am very attracted to you. So how about we see each other soon?” And yet, after the other woman reveals that she’s trans, the first one does a 180 and rejects her: “I’m just not attracted to trans women.”5

There really is something messed up about that. If you go on a date with someone who gives you that tingly feeling, head back to your place, undress, and discover that special someone has different genitalia than you assumed, would that really make the tingly feeling go away? Probably not. I know I become much more sexually attracted to someone after I get to know them, nudity aside. I’ve even become sexually attracted to people I wasn’t attracted to at first sight after getting to know them. All of which is just further evidence that arousal and genitalia do not go hand in hand.

If we can learn to stop defining biological sex by genitalia alone, we can also stop defining sexual orientation by genitalia alone; this means that the trans experience need not undermine homosexuality or heterosexuality. If you’re attracted to a woman and you find out that she has a penis, maybe you need to explore it, not just run off. Same goes for a man with a vagina. Let’s dare to challenge our preconceptions of what we think we know about gender and sexual orientation—including our own.

Being a cissexist doesn’t make you a bad person. It’s only natural that we’d be cissexist when so much of what we’ve been raised to believe about sex and gender is cissexist. The problem is refusing to acknowledge and challenge prejudiced behaviors or ideas you might harbor. That might not make you a bad person per se, but it certainly makes you guilty of bad behavior. When I refused to hear Jessica, when I reduced her and other trans people to their body parts and adamantly insisted I was not a transmisogynist, I was guilty of very bad behavior indeed.

* * *

In the United States and countries all over the world, people who are trans are pushed to the periphery of society and are frequent victims of physical and sexual violence. They experience discrimination at work and often lose friends and family when they come out. Forty-one percent have attempted suicide. I don’t mean to take away from these issues. My intent is to shine a spotlight on the cissexism many of us inadvertently carry—even if you consider yourself an open-minded, liberal leaning individual, chances are you likely hold some prejudices against people who are trans without meaning to—especially if your interactions with and knowledge of trans people is limited. The important thing is to acknowledge these prejudices in order to overcome them. Because the discrimination trans people face is born of ignorance, educating ourselves and opening up a real dialogue is crucial to overcoming both cissexism and transmisogyny.

If you haven’t done so, I encourage you to watch Amazon Prime’s show Transparent, which humanizes the too-often joked about painful process of transitioning. Follow Jessica’s comic Manic Pixie Nightmare Girls. Stay current with Slate’s LGBTQ section Outward. Read Julia Serano’s Whipping Girl , her glossary, and other books by authors who are trans, as they’re the only ones who can truly help us gain a better understanding of the trans experience. Ask questions, talk openly and earnestly, and expose yourself to anything and everything that will help you accept that women and men who are trans are 100 percent women and men; that being attracted to a person who is trans does not threaten your sexuality or identity; that each and every one of us should be free to define ourselves and not be confined by the genitalia we inadvertently possess. If you know someone who is trans, be supportive. Really listen and allow them to define their own gender experience for themselves.

Notes

1. Many 90s/early 2000s sitcoms are guilty of making jokes at the expense of transgendered individuals, including my beloved Friends.

2. Researching for this article, I learned that reassignment surgery is a sensitive subject and one that many people who are trans prefer not to broach publically—understandably so; we call genitals our “privates” for a reason. In her book Whipping Girl, writer, spoken word performer, trans activist and biologist Julia Serano writes, “It is offensive that so many people feel that it is okay to publicly refer to transsexuals as being “pre-op” or “post-op” (32). Further, she says the details of these procedures are “neither relevant nor necessary for one to understand the experiences and perspectives of trans people” (31-32). Accordingly, GLAAD’s Media Reference Guide urges journalists to avoid over emphasizing the role surgery plays in the transition process.

3. Initially, I used the term transphobic, but Jessica informed me that the term cissexism is more appropriate, as it better encompasses the deep-seated prejudices most people hold against trans people.

4. Because the penis = power in our society, it’s little surprise that so many people reject the idea that a woman can have a penis; such an anomaly threatens to uproot patriarchy, placing this long revered symbol of power in the hands of women in addition to threatening the notion that masculinity is superior to femininity. From Serano:

“In a male-centered gender hierarchy, where it is assumed that men are better than women and that masculinity is superior to femininity, there is no greater perceived threat than the existence of trans women, who despite being born male and inheriting male privilege ‘choose’ to be female instead … In order to lessen the threat we pose to the male-centered gender hierarchy, our culture (primarily via the media) uses every tactic in its arsenal of traditional sexism to dismiss us” (Whipping Girl, 15)

5. This is what’s known as cissexual assumption. From Serano’s Whipping Girl glossary: “The common, albeit mistaken, tendency people have to presume that every person they meet is cissexual (unless they are provided with evidence to the contrary). This transforms cissexuality into a human attribute that is taken for granted. It is an active process that invisibilizes trans people and their experiences.”

Melissa Brooks is Assistant Editor at The Thought Erotic. Her fiction and cultural criticism has appeared or is forthcoming in Gravel, Vannevar, The Molotov Cocktail and Saturday Night Reader.

Melissa Brooks is Assistant Editor at The Thought Erotic. Her fiction and cultural criticism has appeared or is forthcoming in Gravel, Vannevar, The Molotov Cocktail and Saturday Night Reader.

Images courtesy of Manic Pixie Nightmare Girls.

So it’s transmisogyny if it is a trans woman but not if it’s a trans man? Wait, what? After reading the article I kept coming back to the same thing. The author keeps going on about how the person’s genitals doesn’t matter because that’s not what you are attracted to in the first place. But it isn’t as black and white as that.

No you aren’t attracted to just their genitals but when you see someone that matches outwardly what you normally want to get sexy with, you are attracted to them because you assume that the bits underneath are the bits that you like to play with normally.

For example, I like vagina, I don’t like penis. So therefore if I see what I think is a woman I am attracted to them because I assume that they have a vagina. If I find out they have a dick then I am no longer interested because I don’t like dick.

This article seems to put forth that if I find out that there is a dick involved in the equation that if I don’t ignore the dick and continue to date or sleep with the person that I am some how trans misogynist. And I find that pretty disturbing.

This is low level coercion, Seriously this is trying to make people guilty for not having a relationship with somebody they don’t want to.

Transmisogyny does refer specifically to trans women, because misogyny is defined as the hatred of or prejudice against women. Prejudice and discrimination are of course also exercised against trans men, but that would be transmisandry and is deserving of a separate article all together.

You are of course entitled to your opinion, as is the author of the article, whose purpose was to help bring awareness to the issues confronting many trans women, whose voices are often suppressed.

The intent was not to make you or anyone else feel guilty for not being in a relationship with a trans woman, but rather, to encourage you and other readers to consider some of the manifestations of societal prejudice against women who are trans and the (often invisible) privilege that cisgender people hold in our society.