by Liz McGehee

“Faces, I suppose, are a type of torture

to look like one but never be one”

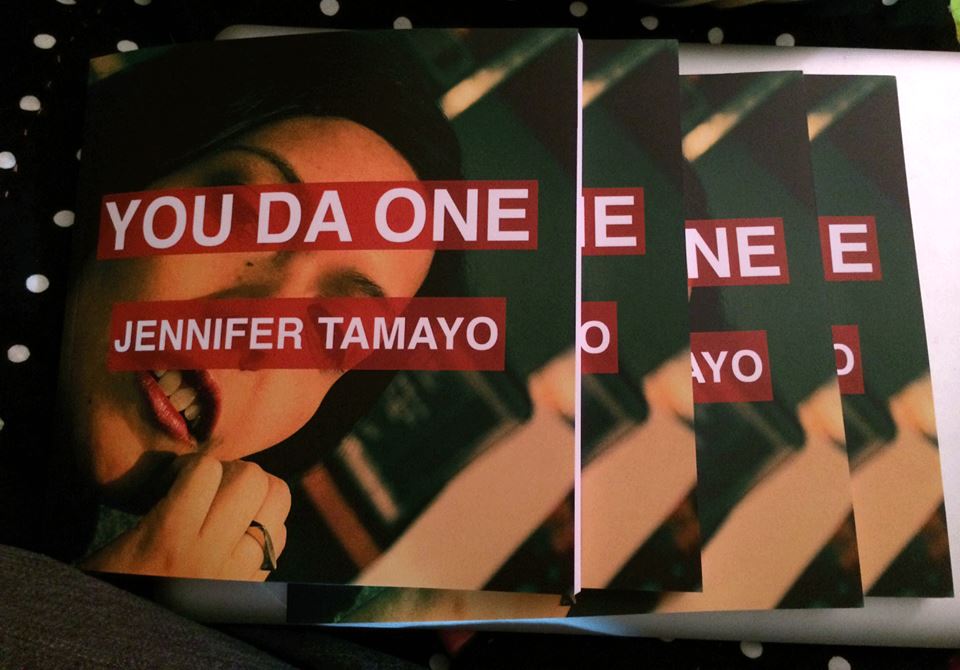

You Da One, by Jennifer Tamayo (Coconut Books), is a rich text brimming with layers—from issues of American assimilation and what it means to be other, to the inevitable self-loathing that comes with being a woman in a capitalistic society bombarded with images, ads and imposed gender and racial roles posing as barriers. In her second book, Tamayo artfully captures what it means to be a woman of color at this time in the United States. In a slaughterhouse of words, abject at times, she takes no prisoners, not even herself. Tamayo rips herself open so that the reader may, for a second, live in her stead.

The speaker we encounter is a cacophony of personal emails, correspondence with family members, self-reflective (and sometimes self-loathing) poems, internet spam, lists of loneliness and pop song lyrics in wildly contrasting font sizes. This mixed media form is disorienting at times—an unrelenting assault of language on every page, the same barrage experienced in everyday life through ads, spam, dialogue, emails, music, images etc., that ultimately comprises our idea of a self and where it fits into American culture.

“I skum magazines, blogs, my favorite books for the

parts in which I can see myself & / clutch me like a

shard”

She births self-assured language and poetic style that defies all parameters; the autobiographical speaker of the poems reads revolutionary. Rarely do we see poets willing to invoke their own name in a piece of work the way Tamayo does, using “Jennifer” frequently in a manner that not only leaves the author vulnerable to her readers, but also refuses to let the reader forget that this a real person and that these feelings and ideas are not abstract things happening in the world. Tamayo’s face, which appears on the cover, is summoned throughout the book as something the reader is forced to confront along with her name and identity.

“where is your face

did you lose your face again, Jennifer

what is the message and why are you going there

the dialogue is saying you are lonely

which someone told you never to say

in a poem”

The struggle of identity and self-consciousness indentured to race and gender is present in every poem. The author questions her looks, her actions, and focuses on what she is and is not allowed to do—always present in the book is an inescapable fear of being wrong.

Variations of the word “English” appear throughout the text and enact the psychological scarring of assimilation in America. In one poem, “englash” is employed as a way to demonstrate how language is expended as a weapon on second language speakers of English and bilinguals. Tamayo appropriates the English language and creates her own meaning through the purposeful misuse of it.

“& when I englash you!

how did my long intestine get on my shoes”

The speaker gives the sense of drowning, whether from the process of assimilating into an overwhelmingly white culture or the sexism instilled in juvenescence that never comes close to abandoning the psyche.

“your mother, she also had hair

your mother, she also had hands

your mother, she was temperamental

In the other’s language—the pang of this word falls on my metals

& my bowels slip and my bowels slip

I’m addressable. Even through time and bodies that are not my own. I’m addressable.”

Similarly, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen explores the same phenomena Tamayo bears witness to with equal candor, that is, “what makes language hurtful.” Rankine quotes Judith Butler in saying: “We suffer from the condition of being addressable. Our emotional openness, she adds, is carried out by our addressability. Language navigates this.” By being addressable, one feels inequality in every interaction, every beauty advertisement or the obvious racial slur. You Da One takes these insidious micro-aggressions/policing and amplifies them to the unignorable.

Tamayo’s poetry comes at an important time in American culture, one in which this wounding idea of the addressable is either met with cheers of recognition or quietly swept back under the rug. Unapologetic in its boisterous, calamitous expression on the page, Tamayo’s voice refuses to be silenced or soothed from its rolling fever of truth. While the reader may have the option of putting the book down, we know that Tamayo, and women of color in general, never have that choice.

For more on Tamayo visit her website or instagram.

Liz McGehee is an MFA candidate at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her work has been featured in New Delta Review, Cloud Rodeo and The Volta, as well as receiving a Pushcart nom and a nom for Sundress Publications Best of the New Anthology.

Liz McGehee is an MFA candidate at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her work has been featured in New Delta Review, Cloud Rodeo and The Volta, as well as receiving a Pushcart nom and a nom for Sundress Publications Best of the New Anthology.

2 thoughts on “An Assault of Language: Jennifer Tamayo’s You Da One”