by Melissa Brooks

The perks and pitfalls of being a tomboy

When I was a kid, being a tomboy was cool. It seemed every girl in my grade claimed to be one whether they really were or not. My friends and I argued about who was the most authentic tomboy. I remember challenging my friend Jennifer’s authenticity because she wore dresses. “Tomboys can wear dresses, too!” she spat back.

We tried to act tough, which amounted to pushing the boys or stealing their baseball caps. We underwent “boot camp” training on the playground, during which a kid named Mike put us to a series of tests assessing our toughness, such as flipping off of the playground’s 6-foot-high metallic bridge.1 I remember feeling triumphant as I overcame my fear and did it, and feeling more triumphant as the-too-girly Jennifer couldn’t work up the nerve.

We revered Christina Ricci’s depiction of Roberta in Now and Then as the quintessential tomboy. She was better than the boys at basketball and ready to throw a punch if anyone dared insult her or her friends. When she developed breasts, she flattened them with duct tape. “That’s what I’m going to do when I get boobs,” Jennifer said, already knowing at age nine that any sign of femininity would deter her from achieving her goals.

I used to think being a tomboy championed the spirit of feminism—I would not succumb to gender stereotypes. I would not be the girly girl my peers, parents and teachers expected me to be. I would be loud, gross and strong.

The problem with my early tomboy aspirations was that they weren’t completely genuine. I didn’t necessarily strive to be a tomboy because I wanted to be one. I did it because I thought there was something wrong with being “girly.”

And I held onto this attitude for a long time, eschewing the overtly feminine like the plague. Even still I don’t wear make up most of the time and when I do, it’s modest. I’m not one for keeping up with the latest fashions. I’m not a “nester.” I don’t color my hair, get manicures or wax. I cannot walk in pumps. I will always dress weather appropriate.

I took pride in my “care free” attitude and appearance while looking down my nose at women who openly embraced their femininity—women too concerned with dress and appearance; women who couldn’t loudly speak their mind when pissed; women who couldn’t hammer a nail or put together IKEA furniture or contend with being in the same room with a bug.

I actively suppressed what seem to be innate aspects of my being, because I feared others would devalue me if I expressed overtly feminine attributes. My sensitivity stands out in particular. It’s always been easy to upset or make me cry. And yet I’ve also always been afraid of crying in front of people or betraying my emotions—even as a child, I knew others would perceive me as weak or unreasonable for doing so.

If someone yelled at me, I quickly excused myself to cry in private. Watching movies at slumber parties, I’d fiercely blink and turn my mind to comedic matters when Leonardo DiCaprio sank into the Atlantic Ocean or when Bruce Willis said his goodbyes to Liv Tyler from an asteroid he was preparing to obliterate. If I ever injured myself, I screwed up my face and squeezed my eyes shut to prevent them from leaking. In college, I went through a period of depression and severe anxiety that instigated daily crying; I locked myself in bathroom stalls in between classes and refused to talk about what I was feeling for fear of looking weak, irrational, like I didn’t have it together. The thing is if I had just talked to someone, if I hadn’t internalized my emotions, I would have been in a much healthier state and probably would not have compulsively cried every day.

While I eventually realized how damaging it is to suppress anxiety and that having emotions does not make you weak, it took me much longer to disassociate the myriad negative connotations yoked to feminine expression as a whole. It was a much harder realization to come to, because belittling femininity in our society runs deep. Our country’s largely dismissive, often hostile attitude towards all things feminine is, in fact, where my longtime fear of betraying my femininity stems from.

Writer, spoken word performer, trans activist and biologist Julia Serano writes extensively about this pejorative attitude towards femininity in her essay, “Putting the Feminine Back in Feminism”:

Female and feminine attributes are regularly assigned negative connotations and meanings in our society … The mistaken belief that femininity is inherently helpless, fragile, dependent, irrational, frivolous, and so on, gives rise to the commonplace assumption that those who express femininity are not to be taken seriously and cannot be seen as legitimate authority figures. (326, 329)

I’ve come to realize how damaging our society’s dismissive attitude towards femininity is. It causes many people to feel ashamed of who they are, leading to feelings of insecurity, worthlessness and unhealthy behaviors to try and suppress certain personality traits. This is true not just for cis women, but also for men and trans women who favor feminine expression.

Pathologizing stylish, sensitive men

Serano uses the phrase “oppositional sexism” to refer to the tendency in our society to view men and women as polar opposites. This means that while femininity is widely devalued, it is also considered a normal or “natural” expression for cis women; male expressions of femininity, on the other hand, are widely considered unnatural, and receive considerable ridicule and belittlement as a result. Serano writes:

Serano uses the phrase “oppositional sexism” to refer to the tendency in our society to view men and women as polar opposites. This means that while femininity is widely devalued, it is also considered a normal or “natural” expression for cis women; male expressions of femininity, on the other hand, are widely considered unnatural, and receive considerable ridicule and belittlement as a result. Serano writes:

If femininity in women is already seen as ‘artificial’ and ‘contrived,’ then oppositional sexism ensures that femininity in men appears exponentially ‘artificial’ and ‘contrived.’ … male feminine expression tends to evoke levels of contempt and disgust that far exceed that which is normally reserved for female masculinity or femininity. (342)

I see this constantly—in my day to day life, in magazines, on television. Contempt for male expressions of femininity runs particularly deep in the sitcoms I grew up with, which often made jokes at the expense of male characters who did anything that fell outside of gender norms. When Joey learned to dance, carried a “man” bag, waxed his eyebrows and made potpourri on Friends, for example, the rest of the gang laid into him for being a “girl.” Even the leading women of the show were ready to insult their male friends for acting like “little girls.” Being girly seemed to become the show’s cornerstone insult.

Serano coined the term effemimania to describe our society’s tendency to pathologize male feminine expression, our “obsession with critiquing and belittling feminine traits in males … Effemimania encourages those who are socialized male to mystify femininity and to dehumanize those who are considered feminine” (342).

It’s hard to deny this—how quick our society is to mock any man who acts remotely feminine. How we cannot seem to fathom the existence of heterosexual men who cry or enjoy shopping or nurture those around them; we automatically deem all men who do these things as gay. How collectively, we mystify feminine gay men and subsequently dehumanize them—even without meaning to. Many well-intentioned people who consider themselves to be LGBT allies treat feminine gay men more as caricatures or even accessories—perhaps to showcase their own “progressive” attitudes—than as real, complex people. Consider the one-dimensional gay best friend character trope so common to romantic comedies that seemed to function like a talking handbag full of witty one-liners to bolster the leading lady’s image, i.e. My Best Friend’s Wedding, Mrs. Doubtfire, even I hate to say it, Mean Girls.

While I may have feared being perceived as weak for crying, at least I could take comfort in knowing that no one would think me “abnormal,” weird or a one-dimensional human being for doing so. But a man who cries will often have to contend with all manner of insults, possible physical assault, and will undoubtedly have his “manhood” called into question. Even the well-intentioned may name him an honorary woman—because “real” men don’t cry.

For these reasons, many gay men purposely distance themselves from feminine expression. As Slate associate editor J. Bryan Lowder wrote in “Do I sound gay? Looks at the lisp”:

Some gay men recoil from “effeminate”-sounding queens, both socially and in the bedroom—a very real dynamic, which, of course, comes down to base misogyny. As Dan Savage points out … many gay men are terrified of being seen as women by the larger culture, and so they predictably bristle at anything that smacks of the feminine.

Typically, we classify derision of male femininity as homophobia, but it’s more than that, especially if you concede that straight men can be feminine, too; it’s phobia of femininity usurping masculinity, of any woman or any person embodying femininity ending men’s stranglehold on power.2

Calling trans women’s identities into question

The widely held perception that feminine self-presentation is inherently frivolous or contrived also presents a problem to trans women who embrace their femininity, as they are often derided for being inauthentic, for merely trying to “mimic” cis women. Their very identities are constantly called into question and they are often accused of perpetuating female stereotypes.

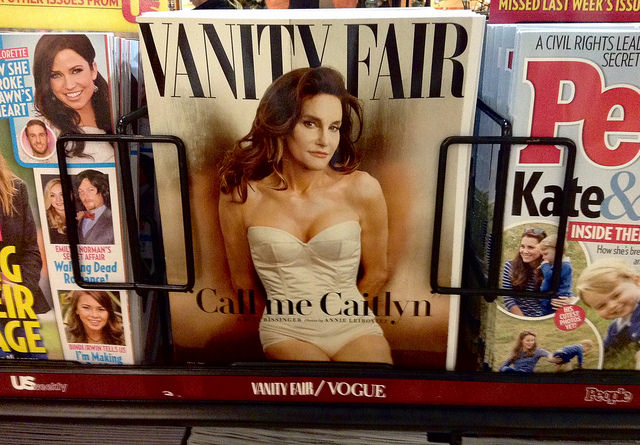

This came up a lot during Caitlyn Jenner’s public transition; in particular, with the release of her hyper-feminized Vanity Fair cover photo. So many articles, op-eds and shows argued over the merits of her transition, her right to call herself a woman, and whether or not she’s a problem for feminism.

For The Blaze, blogger, writer and speaker Matt Walsh wrote:

Parents, be aware: soon the magazine rack in the checkout line at the supermarket will feature this profoundly disturbing image of Bruce Jenner … dolled up in makeup and hair extensions, posing in a corset, with parts of his face, forehead, and throat shaved off for cosmetic reasons, and his chest enhanced by hormone pills … The idea is to make the 65-year-old grandfather look like a college girl, but the effect is that he looks like a distorted version of neither. What he most closely resembles is a mentally disordered man.3

Walsh asserts that Jenner’s physical expression of her womanhood is offensive by perpetuating stereotypes of what a woman “should be.” While they weren’t as derogatory and blatantly offensive as Walsh, many liberal feminists also attacked Jenner for embracing traditional ideals of feminine beauty. In the New York Times Op Ed “What Makes a Woman a Woman?” for example, Elinor Burkett suggested that Jenner’s personal expression of her womanhood insults cis (aka “real”) women, with her “cleavage-boosting corset, sultry poses, thick mascara.” Burkett wrote:

Walsh asserts that Jenner’s physical expression of her womanhood is offensive by perpetuating stereotypes of what a woman “should be.” While they weren’t as derogatory and blatantly offensive as Walsh, many liberal feminists also attacked Jenner for embracing traditional ideals of feminine beauty. In the New York Times Op Ed “What Makes a Woman a Woman?” for example, Elinor Burkett suggested that Jenner’s personal expression of her womanhood insults cis (aka “real”) women, with her “cleavage-boosting corset, sultry poses, thick mascara.” Burkett wrote:

I have fought for many of my 68 years against efforts to put women — our brains, our hearts, our bodies, even our moods — into tidy boxes, to reduce us to hoary stereotypes … But the desire to support people like Ms. Jenner and their journey toward their truest selves has strangely and unwittingly brought it back.

On Slate’s Double X Gabfest, even the progressive Hannah Rosin seemed disturbed by the Vanity Fair cover photo, discrediting Jenner for depicting a cartoonish princess:

It’s like we suspended our irony at what she looked like and the form of femininity that she embodied and just clapped. And that was funny to me. It’s like, it’s 2015, you know, you don’t, when you turn into a woman, have to be this kind of cartoonish woman … In a way it was almost distancing between me and Caitlyn Jenner for her to come out as this kind of woman of the Marilyn Monroe 40s that I barely recognize as a sister.

Of course I don’t want women to be put into tidy boxes or reduced to hoary stereotypes. But Walsh as well as Burkett, Rosin and other exclusionary feminists’ arguments against Jenner’s expression of her womanhood unfairly burden her with the task of representing all women, denying her the right to represent her identity however she chooses.

When we criticize feminine expression as being inauthentic, we deride a significant percentage of women, both trans and cis, as stupid, ultimately undermining their intelligence and self-agency. As Serano writes:

The feminist assumption that ‘femininity is artificial’ is narcissistic, as it invariably casts nonfeminine women as having ‘superior knowledge’ while dismissing feminine women as either ‘dupes’ (who are too ignorant to recognize they have been conned) or ‘fakes’ (who purposely engage in ‘unnatural’ behaviors in order to uphold sexist norms) … It seems incomprehensible that so many women could so actively gravitate toward femininity unless there was something about it that resonated with them on a profound level. (337-339)

Strangely, even Matt Walsh proposed to have this superior knowledge, claiming to understand what defines a woman—“her capacity to create life and harbor it in her body until birth … A woman is a woman because of her soul, her mind, her perspective, her experiences, and her unique way of thinking, of loving, and of being”—and offensively suggests that trans women are being duped, that Caitlyn (who he callously refers to as “Bruce” and “he”) “is being manipulated by disingenuous liberals and self-obsessed gay activists.”

I’m ashamed to admit that I toted this same sense of superiority for much of my life, without realizing the implications of my attitude or the plethora of women who gravitate toward physical expressions of femininity. Now, it’s clear to me that feminine self-presentation must come naturally to many women (not to mention men), and that they do it for their own sense of satisfaction and pleasure. This attitude of superiority then, serves only to continue subjugating and suppressing women by suggesting that they’re inauthentic or too stupid to make decisions for themselves.

Radical feminists, or any person who derides physical expressions of femininity, erroneously equate the individual’s personal experience with the experience of all women. While Burkett may not feel naturally inclined toward feminine self-presentation, while Rosin may eschew the dolled up Marilyn Monroe look, it’s wrong to conflate their personal feelings with every other woman’s. We are all different—our desires, tastes and the way we feel comfortable presenting ourselves. A particular expression doesn’t have to feel comfortable to you to feel comfortable to someone else.

Femininity vs. masculinity—what’s more authentic?

While I know Caitlyn Jenner is significantly more famous, I still can’t help but think of trans model and body builder Aydian Dowling; after being the first trans men selected for The Ultimate Men’s Health Guy and making it to the quarter finals, Dowling didn’t seem to receive the same scrutiny Jenner did for embodying traditional notions of masculinity, and as far as I’m aware of, no one accused him of “mimicking” cis men or being inauthentic. His photos depict “effortlessly” perfect hair, carefully selected jeans to compliment his figure, a six pack and strong pecks.

But why do we constantly call feminine self-presentation—whether in cis or trans women—artificial but rarely question the authenticity of masculine self-presentation? How is spending inordinate amounts of time at the gym any less superficial or contrived than perfecting the cat eye? And it goes beyond appearance to pastimes—with traditionally masculine pursuits considered natural inclinations while feminine ones are considered frivolous. Compare: spending an entire afternoon watching people you don’t even know reenact the pastimes of childhood (i.e. sports) vs. sitting around for a couple hours gossiping over coffee with friends.

We must acknowledge that viewing femininity as “inherently ‘contrived,’ ‘frivolous,’ and ‘manipulative’” allows “masculinity to always come off as ‘natural,’ ‘practical,’ and ‘sincere’ by comparison” (Serano 43).

I’d argue that trans women are derided for feminine expression more than anyone else in our society because by rejecting male privilege in favor of femininity and womanhood, they threaten to expose our culture’s erroneous ideology that masculinity and manhood are superior. As a trans woman, Serano knows this from firsthand experience:

In a male-centered gender hierarchy, where it is assumed that men are better than women and that masculinity is superior to femininity, there is no greater perceived threat than the existence of trans women, who despite being born male and inheriting male privilege ‘choose’ to become female instead. By embracing our own femaleness and femininity, we, in a sense, cast a shadow of a doubt over the supposed supremacy of maleness and masculinity. (14-15)

By rejecting male privilege, trans women give credence to the possibility of a society in which men and women, femininity and masculinity, are equal and every person is allowed to live exactly as they choose—the horror! Those who have a stake in masculinity’s reign deride trans women as fake out of fear that femininity will be seen as superior and masculinity will fall by the wayside—or at least, that they’ll be on an even playing field. This seems like a real step forward for feminism, so it’s disappointing that so many feminists join in on the open derision of trans women and would exclude them from feminism (remember Rosin can’t recognize Jenner as a “sister”).

Walking a tightrope of acceptable traits

By denying women—especially trans women—the ability to express themselves in traditional feminine terms, we end up creating a new ideal that women have to strive for; there is still a “right” way to be a woman. The shape might be different, but we continue to jam women into tidy little boxes. And this new box makes women walk an even finer line that perhaps only Philippe Petit is capable of walking without plummeting to his death. It seems that women now can be neither too feminine nor too masculine, neither too passive nor too aggressive. We must be attractive without trying to be attractive. We must have interesting ideas while remembering our ideas are not as interesting as men’s; we must be careful not to talk too much.

I so often claimed I didn’t want to be a girly girl because I didn’t want to conform to anyone else’s image of what I should be; yet I still molded my personality to what seemed acceptable. I may have been afraid to be overtly feminine, but I was also afraid to be overtly masculine or even androgynous. So I shaved my legs and armpits, tweezed my eyebrows, straightened my hair, and while I may not have wanted to wear dresses, I still wore clothes that flattered my figure. I was obsessive about my weight and wanted to look “effortlessly” pretty.

We must acknowledge that devaluing femininity is a detriment to feminism because it upholds masculinity as superior and makes women walk a tightrope of acceptable traits in order to be taken seriously as a human being or considered a true feminist. Ultimately, feminism needs to be about the freedom to live exactly as one chooses. Every person should be able to dress, behave and present in the way that feels most comfortable and natural to them—so long as it does not harm or infringe on the rights of someone else—without fear of persecution.

If we could collectively learn to see femininity as every bit as legitimate as masculinity; if we could learn to dismantle the negative connotations glommed onto femininity and see it instead as an expression of strength; if radical feminists could open their arms to embrace all expressions of womanhood (and personhood) as legitimate expressions of each individual’s truth and identity, how many more feminine individuals would feel empowered to embrace feminism? How many celebrities who feel their femininity excludes them from feminism would realize that they can enjoy cooking for their husbands and getting ready for dates and being with men and still stand up for the equal rights of women everywhere—and in turn, inspire others to do the same? Let’s recognize femininity for what it is—honest, strong and powerful.

End Notes

1. This isn’t as impressive as it sounds—we weren’t doing standing back flips by any means; we lay on our stomachs perpendicular to the bridge clutching the edges as we somersaulted forward, dangling from the bridge by our fingertips before dropping the foot or two to the ground.

2. What if gay men are ridiculed or assaulted for wanting to “suck dick” because hetero, cis men fear what this feminine-assigned sexual behavior could rightly be construed as: a sign of power? Serano reverses the way we commonly view sexual acts; rather than describing the penis as penetrating the vagina, we could just as easily view the vagina as consuming the penis—and you could say the same for the mouth and ass.

3. I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that this derision of Caitlyn’s appearance is transmisogynist. Those who criticize her expression of femininity target her because she is trans. A cis woman can express her femininity without her womanhood being called into question, while a trans woman often cannot. Accusations that trans women merely mimic cis women and perpetuate stereotypes fail to acknowledge that a trans woman doesn’t choose to be a woman; she has always been a woman. Further, I think it’s safe to say that trans women know feminine self-presentation does not define womanhood, and articles like “What Makes a Woman” presume that trans woman are stupid, and ignore the deep seated identification with womanhood that exists in all women, an identification that has nothing to do with genitals, the ability to pro-create or femininity.

Melissa Brooks is Assistant Editor at The Thought Erotic. Her fiction and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Gravel, Vannevar, The Molotov Cocktail, Saturday Night Reader and Ginosko Literary Journal.

Melissa Brooks is Assistant Editor at The Thought Erotic. Her fiction and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Gravel, Vannevar, The Molotov Cocktail, Saturday Night Reader and Ginosko Literary Journal.

All Images Licensed Under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0:

“Men and Women” by Brian Henry Thompson.

“Caitlyn Jenner, Formerly Bruce, Vanity Fair” by Mike Mozart.

“Lipstick” by Greta Ceresini.

“Heels” by John St John.

Reblogged this on Unwise Woman and commented:

A thoughtful essay written by my dear sister. Read on!